Malaysia's ECRL: Residents in opposition-controlled states laud railway’s benefits, but could it create political tension?

KOTA BHARU/KUALA TERENGGANU, Malaysia: Kota Bharu resident Gan Chin Teng, 60, doesn’t want her home state of Kelantan to lag behind.

“It’s different here,” Gan told CNA, referring to a lack of transport infrastructure such as highways and railways in the eastern coastal state, compared to states on the country’s west coast. “Kelantan needs to be more advanced and not stuck in the past. If possible, we want to move forward.”

This is why Gan, who runs a wholesale store selling household items in the middle of the city, is eagerly awaiting the completion of the East Coast Rail Link (ECRL).

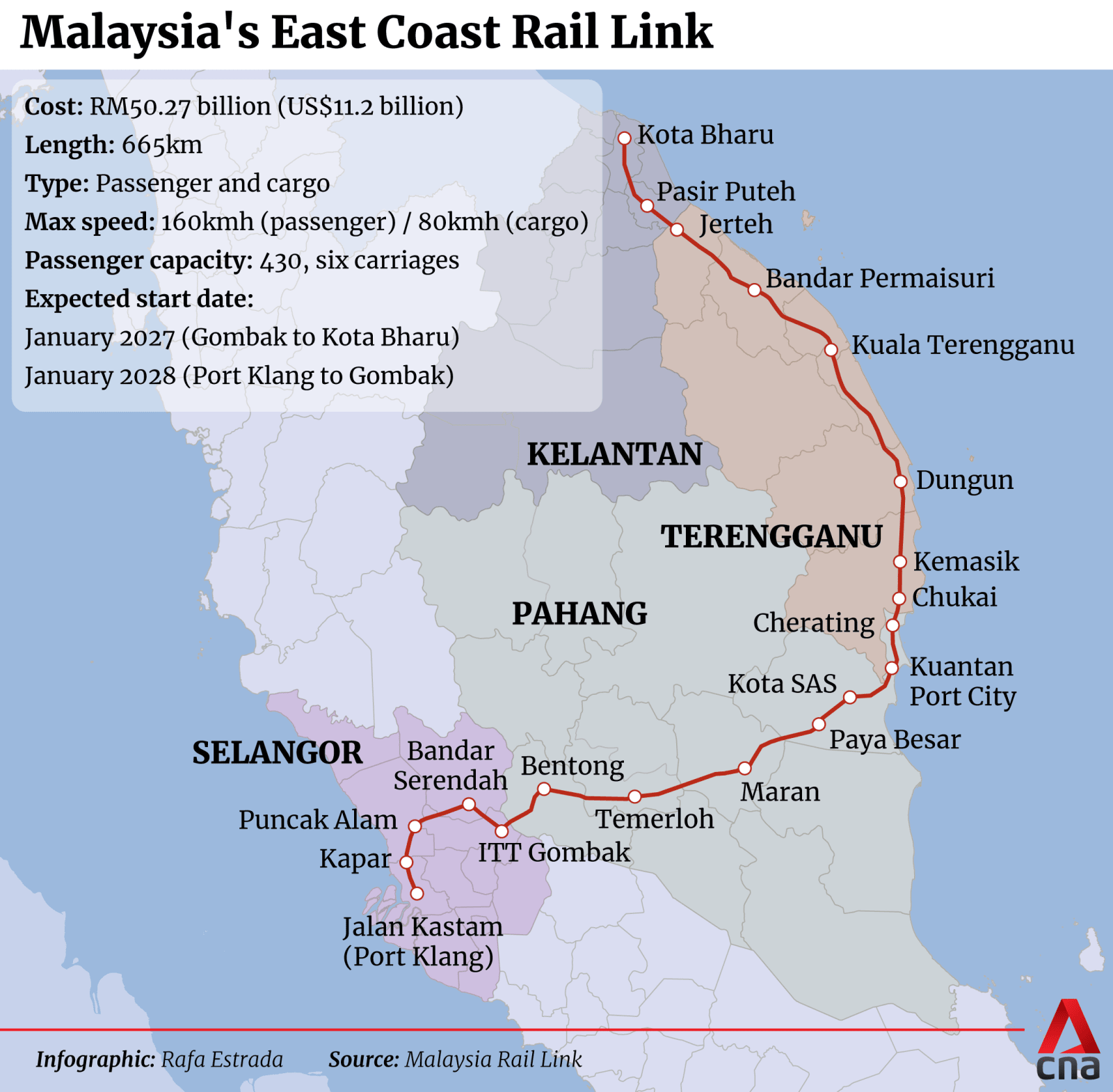

Expected to start operating in January 2027, the ECRL is a major freight and passenger transport project that aims to shorten the travelling time from Kuala Lumpur to Kota Bharu from at least seven hours by road to four hours by rail.

The project is also aimed at narrowing the socioeconomic gap between the west and east coasts by spurring investment and development in the latter’s states of Kelantan, Terengganu and Pahang.

Compared to flying or driving, Gan said the ECRL will give her a safer and more comfortable transport option to Kuala Lumpur, which she visits a few times a year during festivities to see her children.

Beyond these tangible benefits, however, Gan feels the ECRL is exactly the type of infrastructure project needed to give Kelantan an economic boost.

She urged the state government of Kelantan, which has been governed by Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS) since 1990, to be more ambitious in developing the state.

“Everyone in Kelantan will support this project if it can be done quickly,” she added. “We want to see progress here and an upgrade to our infrastructure.”

The ECRL, which was announced in 2016 under the then-premiership of Najib Razak, has a total of 20 stations running through the states of Selangor, Pahang, Terengganu and Kelantan.

More than half of these stations are located in state seats held by the opposition Perikatan Nasional (PN) coalition, which includes PAS and Parti Pribumi Bersatu Malaysia (Bersatu).

CNA spent two weeks last November traversing the length of the under-construction railway, speaking to residents and business owners living around the stations and the cities near them to find out what they think of the project, and the potential political impact of how it has been received by local communities.

People CNA interviewed say they are hopeful the ECRL can create jobs and help local businesses, particularly around the stations, and facilitate travel along the less-connected east coast as well as to and from the west coast.

An analyst pointed out that PN has drawn “dedicated support” within the Malay rural heartland states of the east coast, whose state governments are major beneficiaries of the project through potential economic spillovers and increased state-level revenues.

“This may suggest that there is less likelihood of any substantial opposition to the project from either side of the political aisle,” wrote Qarrem Kassim from Malaysia’s Institute of Strategic and International Studies in the January/March 2024 edition of East Asian Policy.

But CNA’s interviews on the ground also uncovered a less than rosy picture, with the ECRL leaving some negative impact with potential political consequences for both the government and opposition.

Some residents in Selangor - governed by the ruling Pakatan Harapan (PH) coalition - complained about having to give up their homes to make way for the railway, while some Kelantan residents insisted they have suffered from floods caused by the construction of the ECRL.

FEDERAL STATE TUSSLE

Nor Alina Abdul Rahim, who sells crackers at the main market of Pasar Payang in Kuala Terengganu, said she supports the ECRL as she thinks it will give local businesses a leg up by drawing more tourists to the state capital.

While she acknowledged that development in Terengganu - which is currently governed by PN unopposed - has been “slow”, she said she is satisfied with how the state government has performed.

“They have tried to improve on what we have, and I think the ECRL will help to reduce congestion on the roads to the east coast,” the 36-year-old told CNA.

But when Nor Alina was asked if the ECRL’s presence in Terengganu would increase her support for the state government, she felt it would remain unchanged.

“Whatever decision they make, we will live with it. Politics everywhere is the same,” she said.

Independent political analyst Adib Zalkapli told CNA that the current federal government under Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim decided to continue with the ECRL after assuming power in 2022 as the project will earn it “political points”.

The ECRL will lend political credence to unity government parties during the crucial lead-up to the next general election, which must be held by 2027, he said.

“Based on the timeline, the passenger service will likely start when the entire country will be in election mode, so it is important for the unity government to ensure the project is on track,” Adib said.

The China-backed ECRL was briefly suspended under former premier Mahathir Mohamad in 2018 over concerns Malaysia could not pay for it, before being revived the next year to avoid a hefty termination fee.

The fact that the unity government under Anwar continued the ECRL shows that it does not discriminate against opposition-ruled states or constituencies, Adib said, calling this a “major departure” from the Barisan Nasional government’s approach of sidelining PAS-held states in the 1990s.

“It will definitely help the government’s popularity when the passenger service is launched, so the opposition will need more than political rhetoric to challenge the government,” he added.

However, a state politician in opposition-held Terengganu linked ECRL-related development to risks of tussles over federal-state funding, hinting at political tensions.

The ECRL could be used as an example of a project whose state-level development is hindered by the federal government’s perceived reluctance to promptly disburse state-owned funds.

Hanafiah Mat, who is from PAS, urged the federal government to channel Terengganu’s remaining oil royalties directly into the state’s coffers so it can start funding ECRL-related developments.

The state government has already planned projects such as mixed developments, shopping centres, small industries and parks around the ECRL station in Chukai, Terengganu, to create jobs for locals and opportunities for small businesses, he said.

“Our obstacle now is funding,” he told CNA at his constituency service centre in Chukai. “What is slowing this process is the federal allocations that are not being paid.”

Terengganu, an oil-producing state, is currently pursuing efforts to claim royalties of over RM1 billion (US$224.6 million) from the federal government.

Up to October 2023, the federal government was supposed to pay RM1.5 billion in royalties to Terengganu. However, the state government has reportedly received only RM510 million, according to a New Straits Times article last June.

Terengganu says all its expenditures involving oil royalties now require case-by-case approval from the Finance Ministry, and that the federal government is putting “selective restrictions” on the royalties, a claim the federal government has denied.

“We just want to ensure that all allocations directly reach the intended projects … This ensures smooth project implementation and also avoids issues in fund management,” Communications Minister Fahmi Fadzil said last November as quoted by local media.

Despite the lack of funding, Hanafiah - who also holds the state executive council portfolio for infrastructure, utilities and rural development - said the state government is determined to see the ECRL project through.

“Because we know that the ECRL will help the local economy,” he added.

FLOODING CAUSED BY ECRL CONSTRUCTION?

Fatah Salleh, who sells traditional snacks in a market in Chukai, hopes the station there will encourage more domestic tourists to stop by the town.

These tourists currently bypass the area as they usually travel along the main highway to bigger cities on the east coast, he told CNA.

The 68-year-old said he wants to be one of the first to ride the ECRL, counting down the days to 2027 when services start.

“It’s much easier and faster for us to go to Kuala Lumpur or Kota Bharu. Hopefully, I’ll live to see that day,” he added.

“Business now is slower due to the monsoon season. With the station, more people will come.”

But further north in Pasir Puteh, Kelantan, the monsoon has caused flooding in a village whose residents say it only came about after ECRL construction began.

Kasiah Mat Isa, 43, who runs a small convenience store in Kampung Permatang Sungkai just next to the ECRL tracks, told CNA that her village was flooded twice in July during heavy rain.

The first time it happened was in the middle of the night, so she lost her wares to the floodwater that went up to the knee in her shop and the waist outside. As the second flood took place in the day, she managed to salvage her items.

She feels the construction of the tracks, which are on a raised platform, created a physical barrier that stops rainwater from flowing smoothly through her village, causing it to pool there.

“We’ve been told that we would be reimbursed, but it has been months and we have not gotten anything,” she claimed, highlighting that she had initiated the process by lodging a police report with approval from the village chief.

CNA also visited another house in the village that was affected by the floods. The wallpaper in several rooms had badly peeled off, while the damaged legs of some wooden furniture had been sawn off to salvage what was left.

Hasnah Abas, a 67-year-old retiree who lives there, also confirmed that she had not received any compensation for the damage to her home.

In a statement last November reported by local media, ECRL project owner Malaysia Rail Link (MRL) stressed that not all the flooding along the ECRL tracks was caused by the project.

MRL said it was committed to ensuring the project does not disrupt water flow and implementing mitigation measures to reduce flood risks. “MRL will always take responsibility for any damage if it is proven to be caused by the ECRL project,” it added.

In response to CNA’s question on whether those living in areas found to have experienced flooding due to ECRL construction will be compensated, Transport Minister Anthony Loke said last December that MRL must take note of flood-prone areas and introduce flood mitigation measures during construction.

“Any houses which are affected of course will be taken care of by the contractor,” he said.

As the monsoon season intensifies, Kasiah fears that the water levels will rise again. Sure enough on Nov 22 and Nov 28 last year, she sent CNA videos showing her area had flooded again, with children wading in ankle-deep water.

“People from the state government came to visit us, but so far there has not been any help yet,” she said, acknowledging that other communities on the east coast might have been harder hit and would thus need the assistance more.

When asked if her predicament would affect her support for the state government, she said: “I don’t know.”

LACK OF PROJECT ENGAGEMENT

Over in Pahang, residents in opposition-held state seats with ECRL stations had high hopes that the railway would promote tourism.

Muhd Qaiyum Ismail, who sells dried fruit beverages at a makeshift waterfront night market in Temerloh, said the ECRL would help his business by attracting more visitors to his town, which is famous for a type of fatty fish dish called ikan patin.

“There are currently no rail services here, so the ECRL will make it easier for people from the east coast as well as Kuala Lumpur and Selangor to come here,” the 38-year-old said.

The ECRL line then rolls further east towards the east coast, stopping near smaller towns like Maran.

Rosli Amrai, who runs a roadside convenience store outside Maran, said he is unsure if the ECRL will benefit him.

“I don’t think it will help me much because it’s just a station. Those who visit my shop are truckers and people who live around here,” the 46-year-old told CNA, noting that he does not even know where exactly the station will be located.

“People here won’t take the train; I won’t either. We just drive. In the future, some people might stop here, but not a lot.”

The ECRL integrated land use masterplan indicates that the Maran station will be used mainly as a logistics hub to service the surrounding palm oil and automotive industrial areas, although it also highlights ecotourism opportunities nearby.

“If new industrial areas are built around the station, then maybe my shop will get busier,” Rosli added.

A June 2023 study on Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects and their engagement with local communities, published by the Malaysian think-tank Institute for Democracy and Economic Affairs, corroborated some of these sentiments.

The ECRL is a BRI project largely funded by China.

The study also noted that authorities generally make “little attempt” to explain the economic rationale behind BRI projects like the ECRL.

“During our focus group discussions in Pahang, one of the participants observed that the economic rationale behind ECRL was ‘very dubious’, as Malaysia already has roads and railways connecting the east and west coast,” it said.

“They also noted that potential cargo traffic would have little impact on their town, as the town is not a manufacturing or industrial hub, while the distance of the station from the town makes any potential gains from tourism also questionable.”

There is more optimism in Cherating, a quaint beachside town on Pahang’s east coast that used to be wildly popular with foreign tourists but seems to have lost some of its lustre, due to a lack of new offerings and proper promotion.

Mohd Nordin Muhammad, who grew up in Cherating in its heyday during the 80s and 90s and now runs a souvenir store that has stood there for 20 years, hopes the ECRL could be the long-awaited spark that reinstates the town as a choice tourism destination.

Since around a decade ago, long before COVID-19 hit, business at his store had dropped by 30 per cent to 40 per cent, he estimated.

“I am really hoping the ECRL brings Cherating back to its glory days,” the 59-year-old said, highlighting that the turn at a nondescript junction leading to the town could be easily missed by those driving along the main road.

“Cherating doesn’t have tourist infrastructure like an ATM. Hopefully, when the station opens, these types of facilities will be built there.”

Despite that, Mohd Nordin said nobody from MRL or the state government has come to Cherating to explain plans for the ECRL, adding that he only gets information about the project from the news.

This is a point echoed by the Institute for Democracy and Economic Affairs’ study, which noted that for Pahang residents, engagement efforts on the ECRL were made only when the “project directly affects specific landowners, while the rest of the community remains uninformed and excluded from the process”.

“Their main concern is that they were not consulted during the project’s planning and implementation stage, meaning they could not make plans or at least be aware of the negative impacts on their livelihoods,” the study said.

Benjamin Loh, a senior lecturer at Taylor’s University who co-authored the study, told CNA that these issues are unlikely to have a negative political impact at the grassroots level.

Community leaders are wary of making too much noise as they fear losing future development if they are perceived to be “difficult”, he said.

“So, a lot of the complaints are mostly just in demeanour and conduct (of politicians and ECRL officials) instead of any actual negative impacts on environment, economy, etcetera,” he added.

“Fundamentally, any kind of development is always going to result in economic gains for any rural village and so unless the community is forced to relocate, they would often be welcoming of these developments.”

CONTROVERSIAL LAND ACQUISITION

The ECRL land acquisition and relocation process had stirred controversy, particularly in Selangor, with reports of residents railing against what they felt were inadequate lead times before eviction, trespass by ECRL personnel, and insufficient compensation.

These residents live near the planned western end of the ECRL line, in the densely populated areas of Gombak and near Port Klang, and in the lead-up to the August 2023 state polls, the issue threatened to become a political thorn for the Selangor state government.

While PH eventually retained control of its traditional stronghold Selangor, PN almost quadrupled its number of seats in the state.

Zuriana Zulkifli, 44, is among the Selangor residents who have had to give up their homes. She lives near Port Klang in Taman Sungai Sireh, where 89 homes will be demolished for ECRL tracks.

“I feel sad and disappointed,” the homemaker told CNA at the gate to her home, which had a sign that read “no to ECRL”.

“I grew up here, so if possible I want to live here all my life. I like the kampung feel and there are mosques and schools nearby. But if I refuse to move, I will be prosecuted.”

Zuriana, who has lived in the house with her husband - a port worker - and five children for eight years, said she first learnt something was amiss when she was summoned to the local city council in early 2023.

There, she and other residents were told that they had to give up their homes and accept compensation to make way for the ECRL.

The residents rejected the proposal, and after several meetings with authorities made it clear they had no choice, they asked to be given replacement homes instead. This failed too, she said.

Zuriana said residents were offered compensation of between RM400,000 and RM700,000 depending on the size and state of their homes. Her home is larger, so she got RM900,000.

“I feel more at ease now that I’ve gotten the money and found a new place,” she said, explaining that she must move out by December and has bought land to build a new home, still in Klang.

“Houses are expensive now.”

Another resident in Selangor is looking forward to how the ECRL might raise the value of his home.

Raman Rajalingam, who lives in Kapar near a planned ECRL station, said he welcomes the additional transportation option to Kuala Lumpur and Klang, as opposed to braving the often congested roads in the area.

“It’s much easier for me to go anywhere. They are also building a hospital next to the station, which is good for me,” the 57-year-old factory worker told CNA.

“Big projects like this will raise the attractiveness of the homes in the surrounding area. The value of my house will definitely go up.”

Disclaimer: Investing carries risk. This is not financial advice. The above content should not be regarded as an offer, recommendation, or solicitation on acquiring or disposing of any financial products, any associated discussions, comments, or posts by author or other users should not be considered as such either. It is solely for general information purpose only, which does not consider your own investment objectives, financial situations or needs. TTM assumes no responsibility or warranty for the accuracy and completeness of the information, investors should do their own research and may seek professional advice before investing.

Most Discussed

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10