Gunshot wounds, broken limbs: This Doctors Without Borders volunteer treated trauma and injury in conflict zones

One afternoon, miles away from her home in Singapore, Dr Deborah Khoo was attending to a 12-year-old girl with a gunshot wound in her leg. When she and her medical team asked the girl how it happened, they were stunned by her response.

Through an interpreter, they learned that the girl had been shot by her younger brother – who had access to an AK-47 assault rifle.

This is just one of the cases the 35-year-old came across while on a three-month mission in Afghanistan under Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF), also known as Doctors Without Borders.

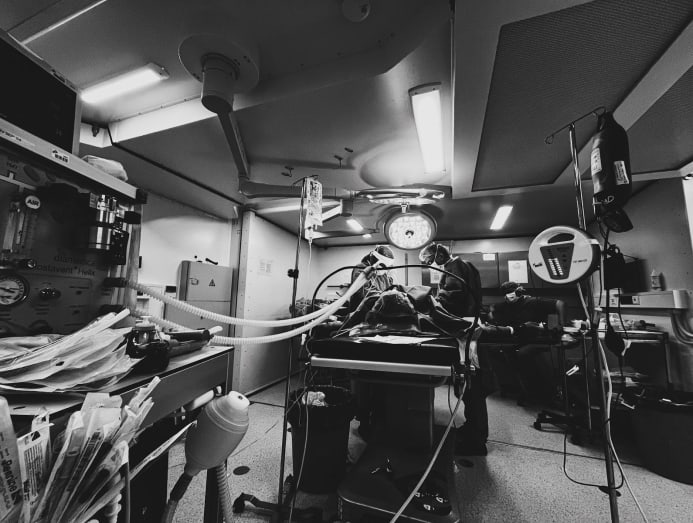

From April to June 2024, the anaesthesiologist at Singapore General Hospital (SGH) was based at the Kunduz Trauma Centre, a healthcare facility run by MSF. Kunduz is a city in north Afghanistan, about seven hours by road from the capital, Kabul.

The centre treats people with trauma injuries, such as from traffic accidents or fights and conflicts. The facility was originally destroyed in a United States airstrike in 2015 and reopened in 2021.

MSF is an independent, non-profit organisation founded in France in 1971 that provides emergency medical aid to people affected by war, epidemics, natural disasters and a lack of access to healthcare. It operates in more than 70 countries, including Ukraine, France, Sudan, Syria, Mexico, India and Thailand.

For three months, Dr Khoo lived and worked with other MSF volunteers at the centre, treating patients like the 12-year-old girl and many others with traumatic injuries in a region where access to safe medical care is rare.

DRIVEN BY A NEED TO HELP OTHERS

Dr Khoo told CNA Women that she had always been drawn to medical humanitarian work, so it came as little surprise to her family when she applied to volunteer with MSF in 2023.

“My mum and my two younger siblings – all of whom are in healthcare – weren’t surprised. They were supportive,” she said. “So were my colleagues at SGH. There were no issues when I applied for unpaid leave to go on the mission.”

There wasn’t a single “aha” moment that sparked her interest in humanitarian work, she said, but the desire to serve people in need, especially in places with the least access to care, had always moved her.

While studying at Duke-NUS Medical School from 2010 to 2014, she joined a few overseas mission trips that lasted from a few days to a week.

One of her first experiences was with Operation Smile, a non-profit that provides reconstructive surgery to children with cleft lip, cleft palate and other facial deformities.

Dr Khoo joined a team in India, where she assisted in cleft lip surgeries and cleft palate repairs for young patients.

“It was my first experience with medical humanitarian work,” she said. “It felt meaningful to help children regain the ability to eat, drink, and have their appearance improved.”

Throughout her housemanship, residency, and even after starting work at SGH, Dr Khoo continued to volunteer for such short medical missions, assisting with surgery in rural communities in places like China and Laos.

SERVING BEYOND CONVENTIONAL HOSPITAL WALLS

The MSF mission is her longest so far. During the application process, Dr Khoo went through extensive briefings by MSF about the potential dangers and risks associated with specific regions.

She had to be open to long-term missions that could last many months, she could be assigned to an area where English is barely used, she had to be open to working with people from different backgrounds, and she could potentially lose her life in conflict areas.

The sobering details didn’t deter her.

When her application was accepted a few months later, she was posted to the Kunduz Trauma Centre in Afghanistan, where she encountered countless cases that tested her medical abilities and reshaped her understanding of what it means to deliver care as a doctor.

“During my mission, I stayed in a reinforced compound within the treatment area,” Dr Khoo told CNA Women. “I had my own room with a bed and a desk, and there was even a small court where people played volleyball when we weren’t working or treating patients.”

Over the three months, she left the compound just five times: Three for short outings, once for a trip to the mountains and the last to fly home.

“In the centre, I worked alongside medical professionals who were incredibly bright and humble,” Dr Khoo said.

One of the Afghan nurses was a medical student. The father of two would make the long commute from his home two hours away. Others included local and international colleagues who balanced their on-ground work with online lectures, studying for exams in medicine, engineering and other fields.

Dr Khoo had to overcome language barriers in real-time medical situations. This could mean breaking down complex English terms like “ventilator trigger” or “physiology of breathing” into simpler language – or illustrating them with drawings to help her colleagues from different countries understand better.

In one case, a terrible traffic accident had left several people injured. Among them was a man who had lost too much blood, and the supply to one of his shoulders was cut off – a life-threatening situation.

“It was really bad,” she recalled. “There wasn’t a blood bank in the area, and he had a rare blood type, O-negative.”

With no access to immediate blood supply, the team had to move quickly. Dr Khoo worked closely with the Afghan nurses and paramedics, discussing possible next steps on the spot.

MSF runs a remote support system where doctors in the field can video call other specialists for advice. For Dr Khoo, that meant reaching out to a medical advisor based in Brussels, Belgium, who could offer technical guidance in real time.

In the centre, I worked alongside medical professionals who were incredibly bright and humble.

“In Singapore, there’s always some kind of emergency stock for blood – and even a backup for that emergency stock,” she said. “Everything is prepared and readily available. As doctors, we don’t always think about where it comes from – we just know it’s there.”

Her time in Kunduz gave her a deeper understanding of the machinery behind the healthcare system back in Singapore.

She said: “The truth is, there are entire departments in the Ministry of Health and hospitals – logistics teams, operations executives – working tirelessly behind the scenes so that doctors and nurses can do their jobs.

“It’s a huge support system we hardly ever see. And admittedly, while we know about it, some of us – myself included – take it for granted.”

“While treating patients and managing pain relief (in Kunduz), I was also constantly aware of how many supplies we had, whether the generators were working, when the next shipment was arriving,” she said. “These were things I rarely thought about at home.

“To save life and limb in an environment where nothing is guaranteed, you’re constantly making tough calls. But I wasn’t doing it alone. Even when we didn’t always agree, it helped to be surrounded by other doctors, medical professionals and people who genuinely cared.”

In the end, the man in the traffic accident did receive a blood transfusion, saving his life.

LEARNING MORE ABOUT HERSELF AND HER ROLE AS A DOCTOR

Seeing conflict zones up close has shifted Dr Khoo’s perspective as a Singaporean doctor. She’s become more mindful, empathetic and open to how healthcare systems function outside of Singapore.

To save life and limb in an environment where nothing is guaranteed, you’re constantly making tough calls.

“Before I went to Afghanistan, I never realised how vast and breathtaking it is – a country of 40 million people, with snow-capped mountains, rivers, plains,” she said.

“Living and working in Singapore, it’s easy to believe the world is orderly, safe, predictable. But it’s not. Even those of us who’ve travelled widely may not grasp how chaotic the world can be.”

That’s not a criticism, she added, but rather a growing appreciation for the places and people she’s encountered – and the perspective they’ve given her.

“These experiences have made me more patient, more accepting, and less quick to complain – especially as a doctor who specialises in relieving pain. These are lessons I’ll always carry.”

She was also especially moved by the strength and resilience of the local healthcare workers and volunteers who support MSF’s work on the ground.

“They come from places that have known conflict for so long,” she said. “This is their everyday reality, and still, they show up. It’s humbling to witness what they do.”

She’s quick to add that humanitarian work is far from glamorous. It’s tiring, emotionally draining and never easy. Some lives don’t get saved, and not every mission feels like a success.

For international volunteers like herself, there’s always a return ticket. But for the locals, this is home. There’s often no reprieve.

“I struggle with that,” she admitted. “There’s a lot I’m still figuring out emotionally. So, instead of trying to make sense of everything all at once, I focus on serving.”

“I’m not the first or only doctor from Singapore to do this – far from it,” she said. “Many of us go because we want to serve. And by sharing our stories, we deepen each other’s understanding of the world.”

To her, the chance to serve in communities far from home is an immense privilege, not because she’s saving lives but because she’s learning, growing and walking alongside others doing the same.

Though the work may be tough, she hopes to return to the field. While MSF volunteers can’t always choose their next mission, Dr Khoo has indicated interest in areas including the occupied West Bank or South Sudan.

“People might think they’re lucky to have us come and help,” she said. “But really, I’m the lucky one. I learn so much every time and look forward to serving again.”

CNA Women is a section on CNA Lifestyle that seeks to inform, empower and inspire the modern woman. If you have women-related news, issues and ideas to share with us, email CNAWomen [at] mediacorp.com.sg.

Disclaimer: Investing carries risk. This is not financial advice. The above content should not be regarded as an offer, recommendation, or solicitation on acquiring or disposing of any financial products, any associated discussions, comments, or posts by author or other users should not be considered as such either. It is solely for general information purpose only, which does not consider your own investment objectives, financial situations or needs. TTM assumes no responsibility or warranty for the accuracy and completeness of the information, investors should do their own research and may seek professional advice before investing.

Most Discussed

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10