Commentary: CDL's father-son feud exposes governance pain points in family businesses

SINGAPORE: The City Developments Limited (CDL) boardroom battle has all the makings of a Taiwanese drama - a billionaire patriarch, a son fighting for control and a Taiwanese music star accused of being the source of discord between father and son.

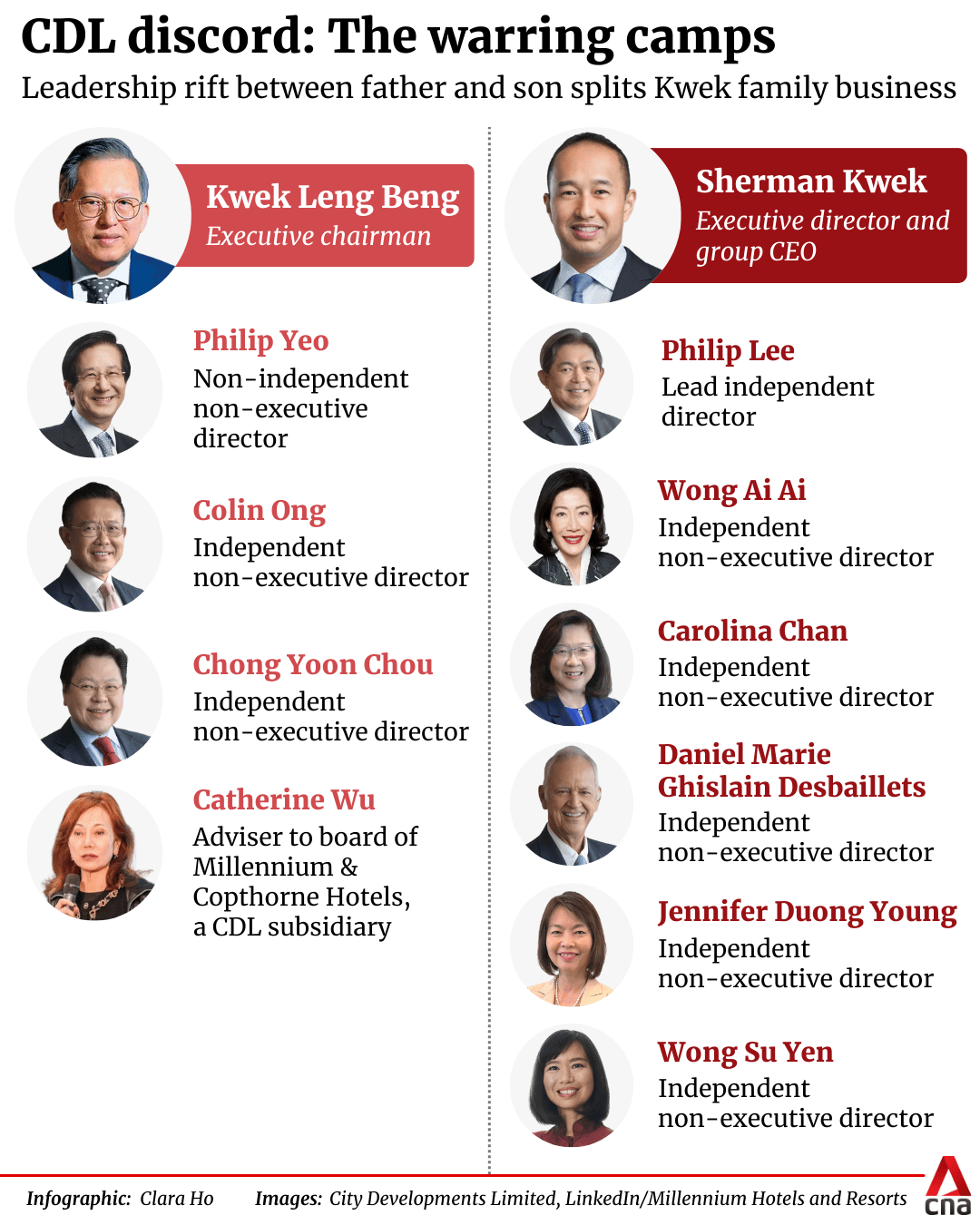

The high-profile feud at Singapore-listed CDL has shaken investor confidence in one of the country’s most prominent companies. Shares in the property giant plunged to a 16-year low after trading resumed on Monday (Mar 3), following executive chairman Kwek Leng Beng’s Feb 26 statement accusing his son Sherman Kwek of attempting a boardroom "coup" and moving to sack him as group CEO.

There is a famous Chinese saying about wealth not lasting beyond three generations and indeed it has been estimated that 95 per cent of family businesses do not survive beyond that.

If the Kwek family wants to be in the 5 per cent and not the 95 per cent, it needs to sort out its family and business governance.

.jpg?itok=flFoqN2X)

KEEPING IT IN THE FAMILY

Singapore has long been home to family-run conglomerates that have helped shape its economic success. But the feud at CDL, which has spilled into court - another closed-door High Court hearing is scheduled for Mar 4 - reveals the risks of entrenched family control.

While family businesses often outperform non-family businesses in the longer term, generational succession doesn’t always translate to better leadership as personal relationships can cloud corporate decision-making.

Some family businesses evolve to professional management with the family retaining control. Others continue to be both family-owned and managed.

In Singapore, we see the different models in two of the three listed banks. OCBC has long transitioned to professional management while continuing to have significant family ownership. There is only one member of the founding family on its 10-member board, and it has had non-family members as CEOs for decades. Meanwhile, UOB continues to have significant family ownership and a family member as CEO, who is currently also deputy chairman.

Which model works better?

Globally, we see successful examples of both models. Bechtel Corporation in the United States and Victorinox in Switzerland have family members as CEOs, while Walmart and L’Oreal retain family control but have non-family members as CEOs.

In Asia, Tata Trusts set up by the family still control Tata Group in India, but the current chairman and CEO is not a family member. Meanwhile, the Ayala family in the Philippines continues to control and manage the eponymous group, with Jaime Augusto Zobel de Ayala from the seventh generation as chairman, and until August 2022, his younger brother Fernando Zobel de Ayala as president and CEO. When Fernando resigned for health reasons, Ayala appointed Cezar P Consing, a long-time executive and a non-family member, to replace him, rather than accelerating the rise of the next-generation family members.

SUCCESSION RARELY GOES PERFECTLY

Succession planning is crucial for all companies but is especially critical – and often neglected – in family businesses. It requires careful consideration of unexpected events, as well as the availability, suitability and readiness of family members to assume senior leadership roles.

Even the best-laid succession plans can unravel. Whether transitioning to professional management or continuing with family management, things do not always go as planned.

A highly successful professional executive may not succeed in a family business due to differences in governance and management style.

In 2011, Tata Group broke away from tradition and appointed non-family member Cyrus Mistry as deputy chairman of Tata Sons after Ratan Tata endorsed him as his successor. Mistry assumed the chairmanship a year later, but differences soon cropped up and he was ousted in 2016 under very bitter circumstances and Ratan Tata returned as interim chairman. In 2017, Natarajan Chandrasekaran became the third non-Tata family member to be chairman of Tata Sons.

A lack of proper succession planning can also have catastrophic consequences. In South Korea, Hanjin Shipping – named Korea’s Best Company in 2016 – went bankrupt in 2017 after the death of the second-generation heir left the chairmanship to his unprepared spouse.

GOVERNANCE CHALLENGES IN FAMILY BUSINESSES

As family businesses grow, governance issues become more complex. Conflicts tend to increase as members of various generations taken on different roles as shareholders, directors, executives or employees. Some rely on dividends, while others draw salaries, making employment and remuneration policies important governance issues.

Family governance mechanisms such as a family constitution (which sets out the family vision, mission, values and policies regulating family members’ relationship with the business), family meetings, family assembly or forum, family office and family council may become necessary.

CDL is just the latest case of a bitter dispute in a listed company. Similar disputes have plagued other businesses in Singapore and across Asia.

In Singapore, we have seen it in companies such as Chemical Industries and Hwa Hong (which has since delisted). In Malaysia, glove manufacturer Supermax saw a bitter fight erupt when the family patriarch’s decision to replace a corporate jet led to a public standoff between him, his wife and two daughters. In Taiwan, Evergreen Group fell into chaos after founder Chang Yung-fa’s death, with his sons contesting the authenticity of his will and battling for control.

Family businesses that hope to continue to flourish must be open to having external professional managers run the business, either permanently or as a transition if there are no suitable family members who are ready.

There are too many listed family businesses that seem too keen to appoint inexperienced family members to senior roles.

CDL appointed an outsider, Grant Kelley, as group CEO in 2014, and within three months, third-generation Kweks were appointed to senior management positions. Sherman Kwek was appointed as chief investment officer and was also CEO of the subsidiary CDL China, while Kwek Eik Sheng became chief strategy officer.

Sherman Kwek became deputy CEO in September 2016 and CEO-designate the following year after Kelley resigned and officially took over in January 2018.

Under his leadership, CDL suffered a S$1.9 billion (US$1.42 billion) loss from an investment in China’s Sincere Property Group in 2020. Critics have questioned whether he would have survived in the company had he not been Kwek Leng Beng’s son.

Given CDL’s poor financial performance, it’s not surprising there are questions if the younger Kwek was the right choice or whether he was made group CEO too early. In his Feb 26 statement, Kwek Leng Beng himself accused his son of making business decisions that put CDL “in a precarious position”.

Both sides in the CDL dispute have been using good corporate governance as the basis for their actions, but warning signs were there long before the conflict erupted.

For example, having both an executive chairman and a group CEO from the same family, while not uncommon, is not ideal. And while Singapore’s Code of Corporate Governance allows an executive director to be on the nominating committee (NC), a wholly and truly independent NC would have been better.

Finally, the resignation of Kwek Leng Beng’s cousin, Kwek Leng Peck, in October 2020 citing disagreements with the board and management over the Sincere deal and the management of Millennium & Copthorne Hotels was an early red flag. His exit was followed by the departure of three independent directors, two of whom cited an investment disagreement as the reason.

CAN CDL AVOID THE FATE OF THE 95%?

CDL’s leadership has tough decisions ahead. It must ask itself if it can afford to continue with family-led leadership given the ongoing turmoil?

If CDL wants to rebuild credibility, it may need to be more open-minded about non-family leadership. However, external professional executives can only succeed if the family takes a step back from day-to-day management and restructure the board.

I would add a word of advice here for all family businesses - not just CDL: Avoid appointing independent directors who are family friends. Not only might these individuals lack the necessary skills and experience, they may only tell management what they want to hear. They can also become a liability when family disputes arise and they are perceived as aligning with certain factions rather than acting in the company’s best interests.

Finally, the Code of Corporate Governance should place more emphasis on issues specific to family-controlled and managed companies, which are very common on SGX. Family companies should also be encouraged to disclose their family governance mechanisms to demonstrate how they manage disputes and ensure that family members contribute to good corporate governance and management of the business.

Mak Yuen Teen is Professor (Practice) of Accounting and Director of the Centre for Investor Protection at the NUS Business School.

免责声明:投资有风险,本文并非投资建议,以上内容不应被视为任何金融产品的购买或出售要约、建议或邀请,作者或其他用户的任何相关讨论、评论或帖子也不应被视为此类内容。本文仅供一般参考,不考虑您的个人投资目标、财务状况或需求。TTM对信息的准确性和完整性不承担任何责任或保证,投资者应自行研究并在投资前寻求专业建议。

热议股票

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10