IN FOCUS: Silver, debut, ice and snow – can these ‘economies’ boost China's domestic consumption?

SINGAPORE: This year, China has to confront a crisis like no other - to save its economy, the world’s second largest, as it readies itself for a potential global trade war with the United States.

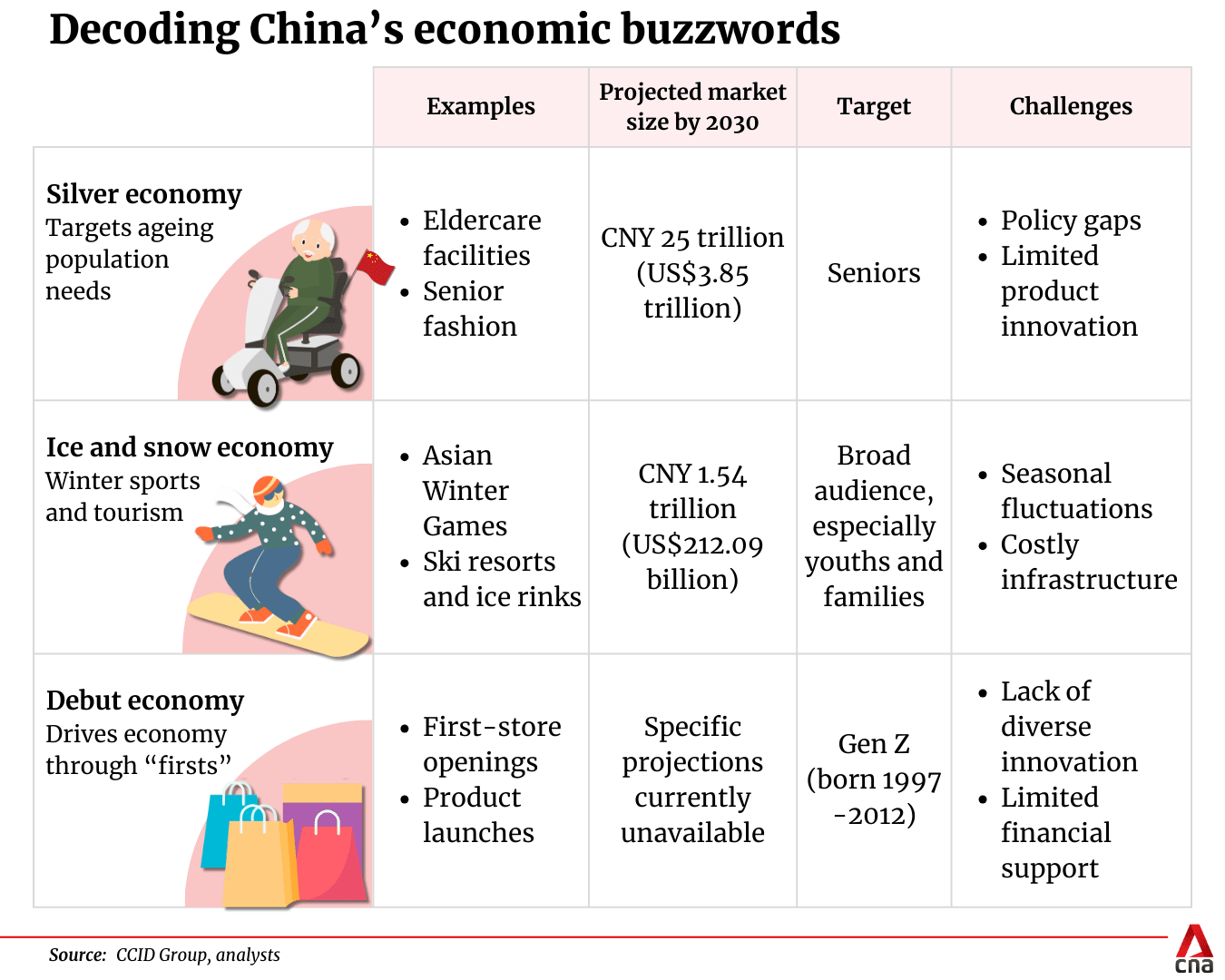

At the heart of its strategy are three new buzzwords: silver, ice and snow, and debut.

The first refers to China's silver economy, products and services catering to the rapidly ageing population.

The second is the ice and snow economy, the country's burgeoning winter sports and tourism industry that is expected to surpass 1.2 trillion yuan (US$165 billion) this year.

There is also the debut economy, the launch of new products, services and flagship stores to influence consumer trends and boost spending.

These three consumption models target different consumer groups and industries and face their own sets of challenges, experts say, but in the long-term, are ultimately designed to complement China’s broader push to boost consumption to shore up the economy.

They “reflect new demands emerging from China’s evolving economic and social landscape” and “intersect in various ways”, said Beijing-based analyst Wang Yuxiong, adding that earnings and successes in recent years had “demonstrated their significant potential for growth”.

But as “emerging economic models”, they also face specific challenges, said Wang, a professor and director of the Sports Economics Research Center at the Central University of Finance and Economics.

“The silver economy faces gaps in age-friendly infrastructure, service standards, and products tailored to the elderly.”

“The ice and snow economy needs to expand its consumer base by increasing participation in winter sports.”

“The debut economy requires further enhancement of the supply-side innovation ecosystem, particularly in terms of financial support, venture capital, and patient capital.”

“Addressing these will be crucial for their sustainable development,” Wang added.

SILVER ECONOMY: SPENDING WHILE AGEING

China's rapidly ageing population is fueling a silver economy boom, industry observers say, with increasing demands for senior-friendly specialised products, services and facilities.

The industry, currently valued at 7 trillion yuan, is projected to hit 30 trillion yuan by 2035.

By the end of 2024, China had more than 300 million seniors aged 60 and above, making up roughly one fifth (22 per cent) of the total population. Experts project that figure to reach 400 million by 2035, accounting for over 30 per cent of Chinese society.

With seniors fast becoming a key financial pillar with growing spending power - developing the silver economy remains a national priority and businesses are moving quickly to cash in.

“The elderly are the biggest beneficiaries of China’s economic miracle and are willing to spend either for their own sake or on their children's behalf,” said Xu Tianchen, a senior economist at the Economist Intelligence Unit.

“While retirees have the money and leisure to spend, they sometimes struggle to find the type of products and experiences that really appeal to them.”

As more Chinese seniors seek support, services must move beyond mainly targeting those without income, family or the ability to work - and cover the wider ageing population, said China’s Minister of Civil Affairs Lu Zhiyuan.

Speaking on the sidelines at a press conference at this year’s Two Sessions, Lu said that the Chinese government is broadening elderly care services, expanding social protection policies and transitioning from basic welfare provision to more inclusive elderly care services.

According to Chinese business data platform Qichacha, there are currently 510,000 silver economy-related enterprises in China. In 2024 alone, 83,000 businesses related to elderly care were registered, marking a record in the past decade.

Cities like Shanghai have been going all out to improve services and living conditions for elderly residents - introducing intuitive services and assistance products while building and developing high-quality care systems.

Shanghai Supermate Intelligent Technology, a tech start-up founded in 2021, is working with a team from the National University of Singapore (NUS) to develop an AI-powered plush toy designed to offer emotional support to lonely seniors.

Product lead Xiao Xin said it focuses on “emotional companionship, psychological therapy, and cognitive rehabilitation”, and “communicates” with users through an app, making use of familiar voices such as family members which offers both therapeutic and cognitive benefits.

“When we started our business, our initial idea was simply to create an AI-powered plush toy,” Xiao told CNA. “However, during market research, we identified key user pain points across different age groups - from children to adults to the elderly (and) found that emotional companionship was a common need among all these groups.”

“The elderly market is substantial but needs vary significantly across different age groups, so it cannot be generalised.”

“Fifty to 70 year olds are generally in good health and more focused on active lifestyles like dancing, socialising and travel,” Xiao said. “Seventy to 80 year olds may require light care support (while) there is an increasing need for medical intervention among 80 to 90 year olds.”

Senior-friendly leisure activities and entertainment have been particularly lucrative business opportunities as more retirees look for new and enriching ways to pass their time.

Karaoke is increasingly catching on with Chinese seniors in cities like Shanghai, who have been signing up for KTV packages, some of which include two meals and access to KTV private rooms for just over 100 yuan.

Others have turned to hobbies like writing dedicated personal memoirs - passing down important memories and beliefs, even engaging professional writers to help tell their stories.

One entrepreneur, a part-time writer from Guangdong province who launched a memoir writing agency using AI tools, previously told CNA he was seeing more business inquiries and requests from elders to help pen their memoirs and turn them into books.

“China’s silver economy is taking off so I looked into starting my own business in this field,” said He Shuyue. “In the final stages of one’s life, people reflect on whether they feel proud of their accomplishments or regret their past. Memoir writing in a way, fulfils that purpose.”

Investing in the silver economy was both an “economic must and social responsibility” for China’s government amid the country’s economic recovery, said Lee Kok How, an affiliate lecturer at the Singapore Management University (SMU).

“Policies that improve healthcare, develop elderly-friendly products and cater to retirees’ needs will boost spending,” Lee said.

ICE AND SNOW ECONOMY: TURNING SNOW INTO GOLD

When Canadian businessman Guy J.E. Cloutier first entered China’s winter sports scene back in 1997, ski slopes were mostly frequented by elite athletes and tucked away either in Beijing or up in the icy northeast.

Today he sees an entirely different picture.

“Every Chinese province and major city has such facilities now,” said Cloutier, who has more than 40 years of experience in the industry, even designing and building China’s first commercial ice skating rink in Beijing.

Ice skating rinks in shopping malls and ski resorts are “pretty much everywhere” in China now, he told CNA.

There are also more buildings and facilities dedicated to offering traditional winter sports like figure skating and track skating. “We can say now that there is a real economy (in China) - winter sports being developed for millions of users, skiers and skaters of every age group.”

“We are also now starting to (see) a real grassroots development with schools and academy programmes,” he added.

“I think within the next 10 to 15 years, China’s (ice and snow economy) will be difficult to beat.”

China’s lucrative multi-billion dollar ice and snow economy is thriving, industry observers say, and is targeting to reach a total market size of 1.5 trillion yuan in 2030, with better infrastructure and enhanced services.

Even as global climate change brings about rising temperatures and shorter winters, winter sports activities and tourism are no longer confined to cold cities like Harbin.

Recent openings of massive indoor ski resorts in cities like Shanghai and Shenzhen over the past year have been feeding the public’s ferocious appetite for winter sports all year round.

Hong Kong native Lorraine Lam, who has worked in the Chinese winter sports and tourism industry since 2019, said the industry only gained traction after China won the bid to host the 2022 Winter Olympics held in Beijing, which spurred significant public interest and led to a “ice and snow economy” boom.

Almost everyone now has basic skiing and snowboarding certificates, said Lam, who is also a certified instructor, working at Karoo Ice and Snow World, the largest snow and ski resort in Shenzhen.

“What’s really interesting is that a lot of people come (to China) to join the ski and snowboard (industries) because it’s so easy to get (certified as) an instructor,” she told CNA.

To encourage and promote the growth of the winter tourism industry, Chinese President Xi Jinping once said: “Lucid waters and lush mountains are invaluable assets - and so are ice and snow.”

The ice and snow economy is fast becoming a core component of Beijing’s domestic consumption push and there has been a concerted effort by authorities to develop and promote it as a new growth sector.

And it’s a strategy that works. Since the start of the latest snow season last November, ski resorts across the country logged over 190 million visits, according to statistics released by the General Administration of Sport body on Mar 11, marking a 23 per cent rise from a year ago.

A total of six snow sports-related jobs and roles were also added to China’s official occupations list in 2024, which include titles such as snowboard repair engineer, ski track planner and skate technician.

China’s ice and snow economy is one that specifically targets the middle class and regional spending, said Wang Dan, China Director at the Eurasia Group, a political risk consultancy.

Foreign tourists have also been showing up in greater numbers, officials say, with overall spending at ski resorts surpassing 35 billion yuan over the past snow season.

Authorities are now anticipating the sector to generate 630 billion yuan in revenue this year, with the market on track to reach 1.5 trillion yuan by 2030.

“Winter tourism subsidies will help the regions that rely on seasonal attractions,” said SMU lecturer Lee.

“While this support is welcome, the gains relative to the entire economy will be small.”

According to a 2024 - 2025 Ski Tourism Forecast Report released by the Beijing Sport University Sports Leisure and Tourism College and China Telecom Wenxuan Technology Company in February, there are 59 registered indoor ski resorts across the country.

The majority are located down south and serve as tourism business models - going beyond being just ski slopes. They are massive snow tourism complexes, integrating entertainment and lifestyle venues to boost tourist spending.

They are complete integrated entertainment hubs blending lifestyle consumption with local development.

In September, Shanghai opened the world’s largest indoor ski resort, the L+Snow Indoor Skiing Theme Resort part of a sprawling integrated tourism and entertainment complex boasting man-made snow slopes and alpine themed attractions like fake mountains, Swiss-style chalets, snow trains, ziplines, cable cars and chair lifts.

The facility spans about 98,800 square metres and has significantly boosted the industry, operators say, as more consumers prioritise spending on health, entertainment and lifestyle experiences.

But challenges still remain, a representative of L+Snow Indoor Skiing Theme Resort told CNA, particularly with regional imbalances and seasonal weather influencing demand.

“The industry is highly seasonal,” the representative said, declining to be named.

“But as more indoor resorts open, skiing is no longer limited by geography or weather. When outdoor slopes close, many head to places like our resort to keep going, even (during) the ski off-season.”

DEBUT ECONOMY: NEW PRODUCTS, STORE LAUNCHES

New services, product launches, the opening of flagship stores - Chinese shoppers’ appetite for new things and trends powers what policymakers call the debut economy model.

“Its success can be tracked through the number of flagship store openings, product launches, industry exhibitions and landmark innovations like the rise of Hangzhou’s ‘Six Little Dragons’,” said Prof Wang, referring to a coalition of tech start-ups, including Deepseek whose AI chatbot roiled Silicon Valley companies earlier this year, that transformed the historic city into a creative innovation hub.

In December, a new commercial plaza opened to much fare in Guangzhou as part of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area (GBA) - featuring more than 80 stores - flagship, concept - spanning across luxury retail, fine dining, and experiential offerings.

The Canton Tower Plaza achieved an occupancy rate of over 95 per cent by the end of last year, Project Manager Jiang Nan told local media earlier in March.

The plaza also drew 310,000 visitors on opening day and over 800,000 in the first three days, generating more than 12 million yuan in sales. Daily foot traffic typically ranges from 40,000 to 60,000 visitors, rising to 80,000 to 100,000 during holidays, and peaking at nearly 280,000 on occasions like New Year’s Eve.

“In the consumer sector, it is actually supply that determines demand,” Wang said. “The debut economy (model) requires further enhancement of the supply-side innovation ecosystem, particularly in terms of financial support, venture capital, and patient capital.”

Shenzhen Tonghe Indoor Ecological Technology, an environmental and social-focused startup, is preparing to open its first physical office space in Shenzhen within the next two years. combining research and experiential functions to refine its smart ecosystem.

General manager Li Hechen says the company sees the debut economy model as a key catalyst driving China’s evolving retail landscape. “It meets diverse consumer demands, unlocks new spending potential and (has become) a new driver of consumption growth,” Li told CNA.

Eligible businesses, brands, stores and companies in Shenzhen, both domestic and well-known international brands, are entitled to receive generous subsidies of up to 1 million yuan, covering as much as 50 per cent of investment costs, including renovations and rent - a policy that Li hopes to leverage.

“It will definitely encourage us,” Li said. “We have very high standards for opening a first store so the initial investment will be relatively large.”

“Receiving subsidy support would certainly ease the burden,” he adds. “We are, of course, still in the process of learning more about and coordinating with the first-store policy.”

Other local governments are also sweetening the deal. In Shanghai, rewards of up to 1 million yuan are offered to global brands and companies looking to open their first stores in Asia.

Subsidies to support both domestic and foreign brands making their debut in Guangzhou can go up to 3 million yuan.

But industry experts and observers say that supply-driven growth has its limits - and warn that China’s brick-and-mortar retail sector is already under strain.

According to a 2024 report released by Euromonitor International, one in five offline retail stores shut down in China each year - and with around 10 million physical stores across the country, that could translate to as many as two million store closures annually.

The debut economy model also taps into the digitally savvy Gen Z demographic. But Wang warns that its targets “mostly young people - a small segment of the population”.

Other challenges are growing.

While promoting and championing the debut economy model to spur spending and nurture fresh brands, it is important that the Chinese government “does not choose winners”, said SMU’s Lee.

Beijing’s push could blur the lines between state and market roles, he adds. “It should only create an enabling environment.”

“The private sector is best placed to decide which ventures succeed. Light-touch support, like grants or tax breaks, encourages true innovation without stifling creativity.”

A report released by the Bank of China last August described intensifying competition and a wave of sameness, with cities competing over similar brands.

Saturation and limited diversification outside of retail and dining risk capping long-term spending and growth.

Many first stores are also struggling to sustain operations, the report said. “In Wuhan, nearly one in four (new stores) closed between 2019 and 2022. The survival rate of debut retail stores stood at just 72.8 per cent.”

A CONSUMPTION VS GROWTH PARADOX?

All in all, China is relying on domestic spending at a time when it is facing “heavy headwinds” from not just the US but also other countries, experts told CNA.

“The question is really whether China does enough to stimulate domestic demand,” said Xu, who adds: “If enough stimulus is given through subsidies and income transfers, and more efforts are made to tap into unmet demand, I can't see why it wouldn’t work.”

Others say there are limits as to how far these sectors will motivate people to spend.

“In general, it’s almost impossible to raise consumption without rising income and wealth,” said Wang Dan.

“A country’s consumer sector is usually prosperous when wealth accumulates quickly and people feel their income will rise faster.”

“It is usually reflected in purchases of large items like cars as well as services like health care, education and (others) towards the higher end.”

China is undergoing a transition from goods purchases to higher-end services but is “only at the start of this change,” Wang added.

“I don’t think any of them (the silver economy, ice and snow economy, debut economy) will be significant enough to lift Chinese consumption as a whole - just to improve consumer spending marginally, if any.”

“Because without income or wealth growth, any increase in certain types of consumption is likely to crowd out others.”

Authorities have already begun laying the groundwork to track consumption progress.

Statistical systems are being developed to monitor consumption trends, infrastructure growth, and industry performance for businesses and companies contributing to the ice and snow economy.

Benchmarks for success in the debut economy include monitoring the number of flagship store openings and product launches - and the sector has already been seeing results.

As for the silver economy, Prof Wang said: “At present, it can be judged by observing whether the needs of the elderly are (being) better met.”

A corresponding statistical system may be established in future, he adds. While high inflation rates are generally considered harmful, some economists believe that a small amount can help drive consumption and economic growth.

“If inflation is heading up, there's a large chance those demand boosts are working,” said Xu.

But at present, inflation remains subdued.

In March, China’s consumer prices slipped below zero for the first time in over a year, underlining persistent deflationary pressures and prompting authorities to lower the inflation target to two per cent for 2025, from three per cent last year.

“Policies take time to work,” Xu said. “So if these measures are effective, inflation data should improve in six months.”

免责声明:投资有风险,本文并非投资建议,以上内容不应被视为任何金融产品的购买或出售要约、建议或邀请,作者或其他用户的任何相关讨论、评论或帖子也不应被视为此类内容。本文仅供一般参考,不考虑您的个人投资目标、财务状况或需求。TTM对信息的准确性和完整性不承担任何责任或保证,投资者应自行研究并在投资前寻求专业建议。

热议股票

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10